Top elements by key in Apache Spark

The problem

Imagine we are responsible of managing a global music streaming service. We have tons of users playing their favourite tunes every day. Each song play is logged by our system, along with the song's metadata and information of the user playing it. We model this domain using 3 simple case classes:

final case class Song(artist: String, title: String)

final case class User(username: String, city: String)

final case class SongPlay(song: Song, user: User)

We are able to read the data from our data lake to get a RDD[SongPlay] with all the song plays. We will be using the Spark's RDD API, but we could replicate it using the Dataset API in a very similar way.

Imagine now that we want to improve our ads performance segmenting them by city. A thing we can do is calculate the top songs by city and generate a customized ad for each one. That is, we want to transform our RDD[SongPlay] into a RDD[(String, Seq[(Song, Int)])], with the top songs for each city and their number of plays. Let's get on with it.

Natural and naïve approach

The first approach that comes to our mind when we get into the problem is straightforward:

def topSongsByCity(songPlays: RDD[SongPlay], numTop: Int) = {

songPlays.groupBy(_.user.city).map {

case (city, songPlaysCity) =>

city -> songPlaysCity

.groupBy(_.song)

.mapValues(_.toSeq.length)

.toSeq

.sortBy(-_._2)

.take(numTop)

}

}

- We want to calculate the top songs in a city, so we group the plays by city. This transforms our

RDD[SongPlay]into aRDD[(String, Iterator[SongPlay])], where they key is the name of city. - For each city, we group the plays by song. We are now working with a

Map[Song, Iterator[SongPlay]]. - For each song, we can get the number of plays using the

lengthmethod of the sequence of song plays. - Then, we sort the result by the number of plays in descending order.

- Finally, we just get the first

numTopelements of the sorted sequence.

Problems of the naïve approach

Our first approach works just fine in the tests. When we deploy it to production, though, our face quickly changes from happiness to sadness as it starts to fail. We are getting random OOM errors for a few tasks. What is happening?

Grouping data is a natural way of solving problems, but it normally does a lot of work that is not necessary. Firstly, groupBy performs a full shuffle of our data. This means that every song play will be send over the network. Ask yourself what is the total size of the dataset and what's the bandwidth between nodes. Data locality is very important to achieve fast pipelines.

The second problem is ths at our data is skewed by nature. Even with infinite bandwidth (instant shuffle), cities vary in size. Cities like New York will have millions and millions of plays, while a small town will have just a few. When we group by song play and city, we are sending all the plays of a city to the same node. This translates to some nodes finishing in seconds and others taking hours to finish. Even more, RDD's groupBy requires all the entries to fit into the memory of the destination node. The Datasets implementation doesn't require it, but we will still need to process them all in the same node.

Second approach

The main problem of our first approach was to shuffle too early. This ended up causing OOM problems or too much processing per node due to skewed data. To improve it, what if we first calculate the number of plays of each song in a city and shuffle that instead of all the plays?

def cityToSongCount(plays: RDD[SongPlay]) = {

val songCityCount = plays

.map(p => p.song -> p.user.city)

.map(_ -> 1)

.reduceByKey(_+_)

songCityCount.map {

case ((song, city), count) => (city, (song, count))

}

}

def topSongsByCity(songPlays: RDD[SongPlay], numTop: Int) = {

cityToSongCount(songPlays).groupBy(_._1).map {

case (city, songCounts) =>

city -> songCounts.map(_._2).toSeq.sortBy(-_._2).take(numTop)

}

}

Using reduceByKey is performant. Why? because it doesn't shuffle all the values as we did. Firstly, it sums the number of values in each node. Then, it shuffles just the pairs of (value, count), which are finally added in the destination node.

Even though we introduced a big improvement, we are still shuffling all the songs played in a city. Our job will probably not fail, but it will last more than it should. This is because our music streaming service is big enough to provide our users with a huge amount of songs. So, again, big cities will have played millions of songs. Can we do better than that?

The final approach

In our second approach, we delayed the big shuffle from song plays to songs with their number of plays in a city. We did this using a function that does a lot of the work in each node before shuffling data. Can we find a way to do more work like that before shuffling?

We can deduce that, in the worst case, all top songs of a city could have ended up in a single node after counting them. This tells us that the minimum shuffle we must perform to get a correct solution is numTop songs per node. So, we can process the top songs by city in each node and then shuffle them. In fact, we are reducing the shuffled data from $$O(\text{songs} \cdot \text{cities})$$ to $$O(\text{numTop} \cdot \text{cities})$$, where numTop will be a lot smaller than the total number of songs. After shuffling, we just have to repeat the process in the destination node.

A performant way to get the top elements of a sequence

We have ended up reducing our problem to getting the top elements of a sequence both before and after the shuffle. In the first two approaches, we did that sorting the sequence in descending order and tooking the first numTop elements. This required $$O(n \log n)$$ time and $$O(n)$$ space. We can reduce that to effectively $$O(n)$$ time and $$O(1)$$ space using a bounded min-heap.

Bounded min-heap

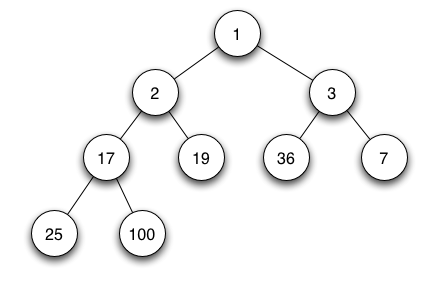

A min-heap is a binary tree such as the data in each node is less than (or equal) to the data in both of its children. This means that the minimum element of the whole tree is at the root.

We can use a min-heap with a little tweak to get the top elements without storing all of them:

- Start with an empty heap, with it's sorting defined by the number of plays in ascending order. Along with it, we will also be tracking the number of elements in the tree.

- For each song, we check the number of elements:

- If it's less than

numTop, we just insert the song into the heap - If it's equals to it, we retrieve the root (the song with the minimum number of plays) and compare it to the song being processed. If the new song has more plays, we remove the current root and we introduce the new song to the heap.

- If it's less than

Retrieving the root can be done in constant time, while deleting it is done in $$O(\log \text{numTop})$$ (logarithm of the number of elements in the heap). Inserting new elements depend on the implementation of the heap, but it ranges from logarithmic to constant time.

The total time of the algorithm is $$O(n \log \text{numTop})$$, but as our numTop will probably be a small number, we can say this is effectively linear. We also just need to store into memory a maximum of numTop elements, so it's also effectively constant space.

Heaps are used to implement an abstract data structure called priority queue. The idea is the same, but priority queues expose 3 methods: offer (to insert and element), peek (to retrieve the min element) and poll (to retrieve the min element and also remove it). Knowing this, we can use the Java's priority queue to implement the data structure whe saw before:

import java.util.PriorityQueue

class BoundedPriorityQueue[A](n: Int, ordering: Ordering[A]) {

import scala.collection.convert.wrapAsScala._

private val underlying = new PriorityQueue[A](n, ordering)

def all: Seq[A] = underlying.iterator.toSeq

def +=(element: A): BoundedPriorityQueue[A] = {

if (underlying.size < n) {

underlying.offer(element)

} else {

val min = underlying.peek()

if (min != null && ordering.gt(element, min)) {

underlying.poll()

underlying.offer(element)

}

}

this

}

def ++=(xs: BoundedPriorityQueue[A]): BoundedPriorityQueue[A] = {

xs.all.foreach(this += _)

this

}

def poll(): A = underlying.poll()

}

Using the priority queue

Now, we just need to use the priority queue to solve the problem for each key both before and after the shuffling. In Spark, this is called aggregateByKey. It takes 3 parameters:

- An empty value for each key.

- A fold function to apply to each element of the key and an accumulated value before shuffling.

- A function to combine the folded values of each node after shuffling.

In our case, the 3 parameters would be:

- An empty

BoundedPriorityQueueof songs and their count, sorted by the count in descending order. - The

+=method of the bounded priority queue. - The

++=method of the bounded priority queue.

def topSongsByCity(songPlays: RDD[SongPlay], numTop: Int) = {

val ordering = Ordering.by[(Song, Int), Int](_._2)

cityToSongCount(songPlays).aggregateByKey(

new BoundedPriorityQueue[(Song, Int)](numTop, ordering)

)(

seqOp = (queue, item) => queue += item,

combOp = (queueA, queueB) => queueA ++= queueB

)

.mapValues(_.all)

// We still need to sort them, as we were storing them in a min-heap

// and we want the top ones

.mapValues(_.sorted(ordering.reverse))

}

Spark has it already!

Luckily, you don't need to implement it yourself. Spark commiters have done it for you. You just need to add the Spark's MLlib dependency, which adds an implicit class to provide more functions to key-value RDDs. Once you add the dependency, it's as simple as:

import org.apache.spark.mllib.rdd.MLPairRDDFunctions._

def topSongsByCity(songPlays: RDD[SongPlay], numTop: Int) = {

cityToSongCount(plays).topByKey(numTop)(Ordering.by(_._2))

}